The Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues presented the Tom and Pat Gish Award to the late Tim Crews, editor-publisher of the twice-weekly Sacramento Valley Mirror in Willows, Calif.; and to the Thompson-High family, who owned and operated for three generations The News Reporter in Whiteville, N.C. The Institute and the Bluegrass Chapter of the Society for Professional Journalists also last night presented the Al Smith Award for public service through journalism by Kentuckians to Becky Barnes, editor of the Cynthiana Democrat, and Murray State University's WKMS-FM.

The Gish Award is named for the late publishers of The Mountain Eagle in Whitesburg, Ky., who exemplified the values of courage, tenacity and integrity in rural journalism for more than 50 years. Their son Ben Gish, who carries on their legacy at the Eagle today, helped choose the winners and present the awards last night at the Al Smith Award dinner at the Griffin Gate Marriott Resort in Lexington. It was the first held without Smith, who died in March.

|

| Tim Crews held up a toothbrush outside a county jail after serving five days in 2000 for refusing to give up an anonymous source (Associated Press photo by Rich Pedroncelli) |

Crews was “one of the greatest fighters for open government at the local level in this country,” said Institute Director Al Cross. Crews died in November 2020, but his widow Donna Settle, who still publishes the Mirror, accepted the award on his behalf in a video. Crews’ propensity for punching up started in kindergarten—literally, in this case: He punched an older bully who tried to steal his milk, she said. He soon fell in love with journalism and set up a darkroom in his parents’ basement as a teenager, selling photos to The Daily Olympian in Washington. After a tour of duty as a Marine in the Vietnam War, he embarked on his career in journalism.

Crews "changed the town forever," said Settle. He ended a sheriff’s career after discovering he was illegally giving gun permits to family and friends. And after a judge ruled his public-records lawsuit against the school district as frivolous and ordered him to pay $56,000 in attorney’s fees on an annual salary of $20,000, an appeals court reversed the ruling.

Between that case and that of the sheriff, Crews "had the attention of the county government and the city government and school district, knowing that when he asked for something, he would fight to get it," said Settle. And when a judge threw him in jail for refusing to reveal his sources, he wrote about it "from jail on little pieces of paper and pencils provided by fellow inmates who admired what he was doing."

Rural journalism was the love of Crews’ life, she said, because it offered many challenges and allowed journalists to deeply engage with their communities. But, when they became a couple, Settle discovered the bravery required of a reporter when she had to get used to seeing local officials in public after writing critical stories about them. “That was a challenge that I hadn’t realized before, and I’m sure practically all good rural, small-town reporters go through the same thing,” Settle said. “You have to stand up to them. Tim never backed down from a good fight on getting the public the open records they were entitled to.”

|

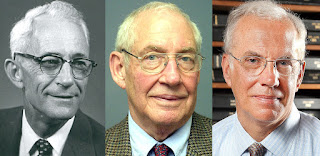

| News Reporter Publishers Leslie Thompson, Jim High and Les High |

The 2021 winners, the Thompson-High family, were no strangers to speaking truth to power. Under publisher Leslie Thompson, The News Reporter and the nearby Tabor City Tribune became in 1952 the first weeklies to win the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service, for their reporting and commentary that quashed the Ku Klux Klan in the county. Thompson “was a principled man who never wavered from his core beliefs,” said grandson and longtime publisher Les High, who accepted the award on the family’s behalf.

"Since then, The News Reporter has continued to show courage, integrity and tenacity by holding accountable local public officials – especially those in the criminal-justice system," said Cross. "The paper has done this despite significant financial adversity, reader and advertiser boycotts, personal attacks and threats against family members; and taking smaller profits to better serve its readers, while always looking ahead. I think it provides an example of how a community newspaper can adapt to the digital age, still perform first-class public service and even extend its reach beyond its home county."

Jim High took over the paper after his father-in-law's death in 1959, husbanding the paper's finance into a healthier state and continuing Thompson's tradition. "He did not shy away from a good fight either," said High. For example, the news paper won a major legal battle in the 1970s to overturn a local judge’s gag order that prevented the them from reporting on a high-profile criminal case.

“My father was my hero. Imagine what a thrill it was for me as a young kid, riding around in his 1965 convertible Mustang, driving to wrecks, fires, bank robberies, still busts, and getting to hang around with the cops in the parking lot," High said. Journalism "got in my blood pretty early."

High sold the paper to editor Justin Smith in August, but says Smith has the kind of spirit needed for the job. Also, they wanted to keep the paper's ownership local. Not content with retirement, earlier this year High launched the nonprofit Border Belt Independent, which provides in-depth investigative reporting for four nearby rural counties. He aims to support the six papers still operating in rural southeastern North Carolina, and hopes the project will be replicated in other rural communities.

He's optimistic about the future of journalism, and said young journalists are "made of the same stuff" as his grandfather and the Gishes. "An increasingly diverse media still produces remarkable stories with smaller staffs, fewer resources," he said. "Reporters do this for little pay, they work long hours, and there are personal attacks where they are cast as the enemy of the people."

But journalists must persevere as is their mission, he said: "Our fragile democracy is under attack, and as we have seen, truth is often the first casualty." He and others present last night "stand on the shoulders of giants who have risked their lives and their livelihoods to tell truth to power," he said. "We owe it to them, our communities, and indeed this nation to persevere with courage and tenacity" despite the challenges.

Chuck Todd agreed. In his keynote speech, MSNBC's "Meet the Press" host said the nation is at war over basic facts. But, though their work has never been more important, "our work’s never been more second-guessed or worse, misconstrued and even attacked," said Todd.

Rural journalists should be lauded because they face a particularly steep uphill battle. "It’s really hard to tell these stories of impact in rural communities, specifically where local politics and kingmakers make it hard to tell these stories, or the fact that you know the person that you’re reporting on," he said.

And rural journalists play a critical role in helping readers understand the local ramifications of the biggest three stories right now, Todd said: climate change, inequality, and the future of this democracy. "Rural journalism is truly a community service," he said. "It’s incumbent upon all of us to be ambassadors for this work."

But readers play a critical role too, he said: "Sometimes being a citizen is active work. It’s not stable right now. All of us play a role. If you’re not in journalism, then support it."

from The Rural Blog https://ift.tt/3vWfLN3 California public-records champion, N.C. family that battled the KKK receive Gish Awards; MSNBC's Chuck Todd: rural journalism 'has never been more important' - Entrepreneur Generations

0 Response to "California public-records champion, N.C. family that battled the KKK receive Gish Awards; MSNBC's Chuck Todd: rural journalism 'has never been more important' - Entrepreneur Generations"

Post a Comment